Recent headlines suggest that prominent technology CEOs are tossing tepid water onto the quantum computing narrative, leading to a sell-off of quantum computing stocks in January 2025. However, quantum computing CEO’s disagree, asserting that commercial quantum computers are already here and delivering value to clients. While the timeline for widespread quantum utility remains debated, one thing is undeniable: innovation in quantum computing is accelerating, and the evidence is clearly visible in the patent landscape. Understanding these patent trends offers a valuable, albeit early, glimpse into the technologies being developed, the companies leading the charge, and the potential challenges along the way. Just as provisional patent applications filed as far back as the launch of the iPhone in 2007 foreshadowed Apple’s release of the Vision Pro headset in February of 2024, the current quantum computing patent activity hints at the future direction of this transformative field. See U.S. Patent No. 15/972,985 incorporating by reference U.S. App. No. 60/927,624 and U.S. App. No. 61/010,126.

What is a Quantum Computer? Moving Beyond Bits to Qubits

To understand the difference between a classical computer and its quantum counterpart it may be useful to think of a classical computer like a light switch. The light switch can be either ON, representing a 1, or OFF, representing a 0. These 0s and 1s, called bits, are the foundation of all the computations that modern classical computers perform.

Now, imagine a dimmer switch instead of a simple on/off switch. A quantum computer leverages qubits that, unlike bits, are not strictly 0 or 1. Rather qubits can exist in a state of superposition. Think of it this way: a qubit can be both 0 and 1 at the same time, or anywhere in between, until it is physically measured. This “both at once” state is the superposition, and it dramatically expands the possibilities for computation. Qubits can also be linked together through entanglement, a quantum phenomenon where their “fates” are intertwined. As an example imagine these entangled qubits are actually two coins that are linked. Even if you separate them by a vast distance, flipping one coin and reading whether it is heads or tails also instantly determines the outcome of the other coin. Thus their “fates” are intertwined and they act as a single system, no matter how far apart they are. This interconnectedness further amplifies their computational power.

Because of superposition and entanglement, quantum computers can explore vast computational spaces far more efficiently than classical computers for certain types of problems. While classical computers tend to tackle problems step-by-step, quantum computers can explore many possibilities simultaneously. This gives them the potential to solve problems that are infeasible for even the most powerful supercomputers.

Overall Quantum Computing Patent Filing Trends in the US

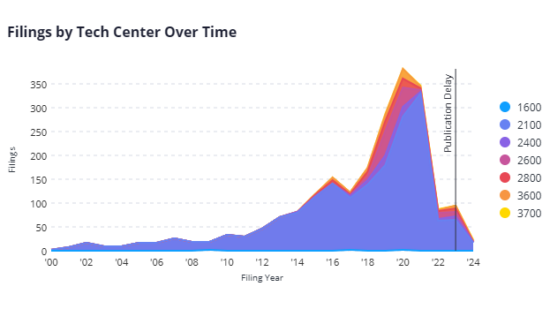

Figure 1: Quantum Computing Patent Filings in the US Over Time

Figure 1 illustrates the overall trend of quantum computing patent filings in the United States. The number of filings started to increase dramatically in the mid-2010s. However, the most recent data points for 2023 and 2024 may appear to show a decrease but it is crucial to interpret this in light of the ~18 month publication delay at the USPTO. Therefore, the filings for the most recent years are still underrepresented in this data, as many applications filed in 2023 and most filed in 2024 are yet to be published. Regardless, the overall trend clearly indicates a robust and rapidly expanding field of innovation within quantum computing.

Top Quantum Computing Modalities: Patent Filing Trends

While the overall quantum computing patent landscape shows strong growth, examining trends within specific physical realization methods, or “modalities,” provides a more granular understanding of the innovation landscape. Here, we delve into the patent filing trends for some of the top modalities, based on our analysis of patent activity: Superconducting, Annealing, Topological, Photonic, Trapped Ion, and Quantum Dot.Rejection Type Analysis: Navigating Patent Prosecution Challenges

Beyond filing trends, understanding the types of rejections faced by quantum computing patent applications is crucial for strategic patent prosecution. Analyzing rejection data provides insights into the patentability hurdles specific to this technology area. Here, we examine the distribution of rejection types for quantum computing patents in the US.

Examining patent filing trends across six quantum computing modalities (Figures 2-7) reveals a nuanced picture of innovation within the field, marked by a noticeable difference in scale. Superconducting (Figure 2) and Quantum Annealing (Figure 3) stand out with substantially higher patent filing volumes, with their y-axes scale depicted up to 80, indicating a significantly greater level of patenting activity compared to the other modalities with their y-axes scale depicted up to 15. Both Superconducting and Quantum Annealing demonstrate robust and sustained upward trajectories, suggesting consistent and major investment in these areas. In contrast, Topological (Figure 4), Photonic (Figure 5), Trapped Ion (Figure 6), and Quantum Dot (Figure 7) quantum computing exhibit considerably lower patent filing volumes. These modalities show more gradual filing patterns: Photonic and Trapped Ion display steady, albeit moderate, growth, while Topological and Quantum Dot are characterized by lower overall patent activity. This disparity in scale may reflect the relative maturity, investment levels, and perceived near-term commercial viability of Superconducting and Annealing technologies compared to the other modalities.

Overall Rejection Type Distribution

Figure 8: Distribution of Rejection Types for Quantum Computing Patents

Figure 8 presents the overall distribution of rejection types for quantum computing patent applications. As anticipated in many technology fields, 35 U.S.C. § 103 rejections based on obviousness are the most frequent, accounting for approximately 30% of all rejections. However, a significant portion of rejections also fall under 35 U.S.C. § 101 concerning subject matter eligibility, representing approximately 15% of rejections. The USPTO’s interpretation of § 101, particularly in the context of abstract ideas and laws of nature, can pose challenges for quantum inventions that may involve algorithms, mathematical methods, or fundamental quantum principles. 35 U.S.C. § 102 rejections for anticipation account for approximately 20% of rejections, indicating that a substantial number of quantum patent applications are being rejected based on prior art that anticipates the claimed invention. 35 U.S.C. § 112(b) rejections for definiteness, also around 20%, suggesting challenges in clearly and precisely defining the scope of quantum inventions in patent claims.

PTAB Case Study: Ex parte Cao – A Victory on Written Description and Subject Matter Eligibility

A recent Patent Trial and Appeal Board (PTAB) decision in Ex parte Cao (Appeal No. 2024-002159) illustrates the challenges and nuances of patent prosecution in quantum computing, particularly concerning 35 U.S.C. § 101 and § 112(a).

In Ex parte Cao, the applicant appealed a Final Rejection that included both § 112(a) Written Description and § 101 Subject Matter Eligibility rejections. The invention related to a hybrid quantum-classical computer system designed for solving linear systems of equations. The proposed system combined classical and quantum computers to leverage their respective strengths in tackling complex mathematical problems. The claims focused on a method and system for preparing a specific “quantum state” that approximated the solution, utilizing a “cleverly designed objective function.”

The Examiner argued that the specification lacked adequate written description for the broad claim term “generating an objective function that depends on . . .” under § 112(a), asserting that the specification provided only limited examples and did not sufficiently describe the genus of objective functions claimed. Furthermore, the Examiner contended under § 101 that the claims were directed to an abstract idea – a mathematical method for solving linear equations – and lacked the requisite “significantly more” to establish patent eligibility, even with the inclusion of quantum and classical computers in the claims.

In a significant win for the applicant, the PTAB reversed the Examiner’s rejections on both grounds.

1. Written Description – Specification Examples Can Be Key for Genus Claims:

The PTAB overturned the § 112(a) rejection, finding the specification did adequately describe the claimed invention. The PTAB’s key reasoning included:

- Specification Provided Examples: The specification detailed specific “objective functions” and provided “specific implementation examples.”

- Functional Characteristics Sufficient: While the claims used functional language (“generating an objective function that depends on . . .”), the PTAB found that the specification, by providing examples and defining the characteristics of a suitable objective function, sufficiently conveyed to a PHOSITA that the inventor possessed the claimed genus.

- Distinguishing Vasudevan Software: The PTAB distinguished the case from precedent like Vasudevan Software, Inc. v. MicroStrategy, Inc., where claims lacked specification support. In Ex parte Cao, the claims were tied to specific elements described in the specification.

When drafting claims with broad, functional limitations, particularly in complex technologies like quantum computing, robust specification support is necessary. Practitioners should not merely repeat claim language in the specification. Practitioners should provide concrete examples and clearly describe the characteristics and functionality. This can be sufficient to establish written description, even for genus claims.

2. Subject Matter Eligibility (§ 101) – Focus on Technological Improvement and Practical Application:

The PTAB also reversed the § 101 rejection, finding the claims were not directed to an abstract idea. The PTAB’s reasoning emphasized demonstrating a technological improvement and practical application in computer-implemented inventions:

- Quantum Computer as More Than a Generic Tool: The PTAB rejected the Examiner’s view of the quantum computer as simply a generic tool for mathematical calculations. They recognized that the inclusion of a “quantum computer, controlling a plurality of qubits . . . to prepare a quantum state” was not just “recitation of gathering data.”

- Integration into Practical Application: The PTAB found this element “represents the focus of the invention and integrates the recited abstract idea into a practical application.”

- Technology Improvement – Enabling Noisy Quantum Computers: The PTAB agreed with the Applicant that the invention provided a “technology improvement” by “enabling noisy quantum computers, which have limited circuit depth, to practically solve linear systems.” They cited the specification’s description of prior art limitations and the invention’s solution.

To overcome § 101 rejections, especially in software and computer-related inventions, practitioners should clearly articulate and emphasize the technological improvement and practical application provided by the invention. By showing how the invention improves the technology itself, solves a technical problem, or provides a tangible benefit in a practical field practitioners can overcome pesky § 101 rejections.

Implications for Patent Attorneys:

- Detailed Specification is Paramount: Ex parte Cao underscores the critical importance of a well-drafted specification, rich with examples and detailed descriptions, especially when claiming complex technologies.

- Focus on Technological Advancement: When facing § 101 rejections, frame your arguments around the technological improvement and practical application of the invention. Highlight how it solves a real-world problem and advances the state of the art.

- PTAB Reversals are Possible: Even in complex cases with challenging rejections, a well-reasoned appeal brief, focusing on the legal principles and supported by the specification, can lead to a successful PTAB reversal.

While quantum computing may seem esoteric, the principles illustrated in Ex parte Cao are applicable and relevant to patent attorneys in various fields. By focusing on detailed specification support and clearly articulating the technological advancements of your client’s inventions, you can significantly increase your chances of overcoming Examiner rejections and securing valuable patent protection.

Data Source and Methodology

Please note that the charts and related information in this article were generated using information provided courtesy of Juristat. The patent data was obtained using custom keyword searches in the Juristat patent analytics platform.

Overall Quantum Computing Trends: The overall quantum computing patent filing trends were generated using the search query: “quantum computer”|”quantum computing”|”qubit”. Where | represents an OR operator.

Modality-Specific Trends: The patent filing trends for each of the six quantum computing modalities (Superconducting, Annealing, Topological, Photonic, Trapped Ion, and Quantum Dot) were generated using modality-specific keyword search queries. These queries included combinations of terms related to each modality, such as qubit types, technology names, and associated terminology.

Search Fields: Searches were conducted within the Title, Abstract, and Claims fields of patent applications.

Rejection Type and Tech. Center Breakdown by Modality Appendix

The following table provides a breakdown of rejection types by modality, offering a more detailed view of the patent prosecution challenges for each technology.

Appendix Figure 9: Rejection Type Breakdown by Modality

While the overall rejection distribution provides a general overview, examining rejection types by modality reveals further nuances. Some interesting findings:

- Superconducting Quantum Computing patents tend to face a higher proportion of 102 (Anticipation) and 103 (Obviousness) rejections compared to 101 rejections. This might suggest that for this more mature modality, the focus of patent examination is more on novelty and nonobviousness over prior art, rather than fundamental subject matter eligibility.

- Quantum Annealing patents, in contrast, exhibit a notably higher percentage of 101 (Subject Matter Eligibility) rejections. This is likely due to the nature of annealing inventions, which often involve algorithms, optimization methods, and system architectures that may be scrutinized for abstractness under § 101.

- Topological Quantum Computing patents show a significantly elevated percentage of 112(a) rejections (Written Description and Enablement). This highlights the challenges in adequately describing and enabling these complex, cutting-edge inventions in patent applications, likely due to the theoretical and nascent stage of the technology.

- Trapped Ion Quantum Computing patents display a higher percentage of 112(b) rejections (Definiteness), suggesting difficulties in clearly defining the scope of claims related to intricate ion trap systems and control methods.